How to handle uncertainties in modelling due to human reliability issues for nuclear disposals

Oliver Straeter

Fabian Fritsch

Modelling plays a crucial role in assessing the design for future technical or geological development of a repository for radioactive waste. Models and the application of these models to scenarios are used to weigh different safety-related designs or to assess the suitability of sites. Even if the models simulate and evaluate a system in a geological context that is designed as a passively safe system, the human factor plays a significant role in the overall assessment process and thus in finding a site with the best possible safety, in accordance with the Site Selection Act in Germany. This influence is not seen at the level of repository operation, as is traditionally viewed with regard to human factors, but rather in the design of the repository – particularly in the decision-making process and the definition of the system's fundamental design parameters. Thus, considerations of human reliability are also of utmost importance for the passively safe system of a repository, especially in the current phase of the search and evaluation process. Given that severe accidents in human-made technological systems depend heavily on the reliability of human behaviour, not only in operation but also in design and conceptualisation, considering human reliability aspects is essential for a successful site selection (Straeter, 2019).

This article first provides an overview of the technical, organisational, cross-organisational, and individual aspects of human reliability that are crucial in the modelling phase of radioactive waste management. Human aspects include variations in the selection of models, the definition of input parameters, and the interpretation of results as individual or group efforts. Based on a review of relevant guidelines on the topic (VDI 4006), suggestions are presented for dealing with these human factors at different levels. The approach is supported by a study on the importance of these factors, which was carried out in the context of the TRANSENS project conducted jointly by the University of Kassel and TU Clausthal. Overall, based on these considerations, the Assessment of Human Reliability in Concept phases (AHRIC) method is proposed to assess the negative effects of trust issues in the site selection work processes and to derive mitigating measures (Fritsch, 2025). The method applies to all work processes of the key actors.

- Article

(708 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The search process for high-level radioactive waste in Germany is characterised by the selection and interpretation of criteria, geological assessments, data interpretation, and modelling of the effects of geological and technical barriers. Even though no operational mine exists and the disposal process has not yet begun, this process is nevertheless characterised by diverse human influences on the reliability of the sub-process. Examples of problems include:

-

Decision-making processes and preferences, as well as the assessment of limitations of predictive models;

-

Uncertainties in the use of predictive models used to define design criteria;

-

Decision-making in reconciling scientific results with other (political or societal) constraints;

-

Conceptualisation and design of disposal processes and facilities in a materials science and geological context;

-

The prospective assessment of the impacts of the operational aspects of storage and disposal.

Operational procedures for assessing human reliability require defined operational conditions (contexts) to estimate the safety impact. These conditions are evaluated based on the specification of activities (work as planned) and the implementation of activities in the real environment (work as done). VDI 4006 (2025a, b, c) defines work as planned as task-oriented behaviour and work as done as goal-oriented behaviour. In the latter case, in addition to the specified activity, requirements from the real environment lead to the need to balance different goals in the work context.

During the search process, the emplacement processes are not yet as precisely specified as would be necessary for an assessment using operational procedures. Nevertheless, the influences of this search and planning phase are crucial and determine essential safety-related properties of the repository.

An assessment of human reliability during the site selection phase is therefore essential. The following section first addresses the issues of the modelling process and the importance of trust. It then shows how an assessment of human reliability can be achieved in this planning phase of the search for a final repository.

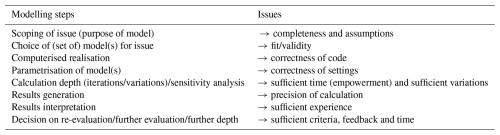

2.1 Issues of a modelling process with importance for human reliability

Human reliability issues in modelling are naturally different from those encountered in the operational management of tasks in a real mine or packaging plant. In order to structure these issues and demonstrate their significance, the steps of a typical modelling process can be used as a basis. When modelling geological facts or the design of a container, for example, different steps must be completed, starting with the scope of consideration and ending with the interpretation of the modelling results. Different people with different concepts and previous experiences are involved in these processes.

These individuals must interpret and evaluate the uncertainties of the modelling using their cognitive concepts and prior individual experiences. In modelling, the completeness and assumptions about system behaviour always play a decisive role, as do the fit of these concepts and experience in assessing the accuracy of a model (Straeter, 2005). Table 1 shows the human reliability issues that can be expected in modelling.

As the table illustrates, different weighing processes must be performed under uncertainty within the framework of a variety of modelling approaches. The people involved in this modelling process must carry out these weighing processes on the basis of their expertise. Their own expertise, consisting of experiences and the concepts developed from them, plays a crucial role, because people are bound to the cognitive processing cycle within the framework of their cognitive processing (Straeter, 2005). This states that an assessment is always based on concepts acquired through individual experience, and any mismatch between these and the information from the world is compared via a central comparator (the limbic system). The comparison always occurs both cognitively and emotionally. The emotional component means that mismatches are evaluated not only cognitively but also emotionally. This results in the devaluation of inappropriate information (under-trust), the search for confirmation of one's own experiences and concepts (over-trust) and the search for simplifications to reconcile one's own experiences and concepts with information. The way in which these simplification strategies take place is known in psychology as biases (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974; Englisch, 2024). Biases enable us to deal efficiently with mismatches in our environment based on our “gut feeling”. On the other hand, this effect grants us a degree of confidence based on our own experiences and concepts in a given situation, which is not necessarily valid.

2.2 Trust and human reliability

Dealing correctly with this mismatch is an issue of correct trust in oneself and the information provided to us in a particular situation. The highest level of reliability is achieved by building a reasonable relationship of trust. Over- and under-trust result in biases. For the task of modelling, this means, for example:

-

Under-trust results in scenarios where appropriate models are not used.

-

Over-trust results in scenarios where inappropriate models are used.

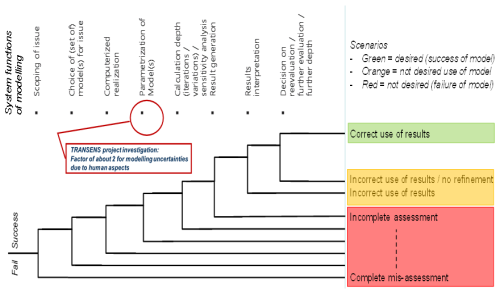

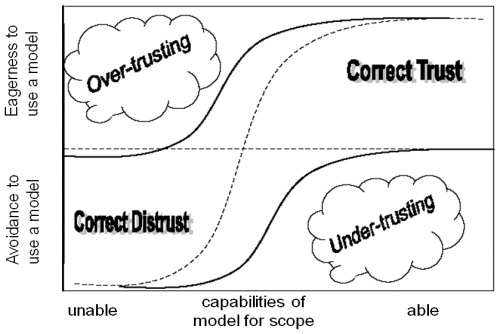

Figure 1, according to EUROCONTROL (2003), describes this relationship between the fit of one's own abilities (experiences and concepts) on the x axis and the cognitive–emotional regulation (solid and dashed ogives) and the resulting behaviour on the y axis.

Figure 1Relationship between own abilities (experiences and concepts) on the x axis and the trust-related cognitive–emotional regulation (solid, dashed ogives) and the resulting behaviour on the y axis (based on EUROCONTROL, 2003).

The human cognitive processing cycle performs a comparison and assessment once a mismatch exists. However, there is a biased relationship between a person's level of trust and resulting behaviour. According to VDI 4006, reliability issues may result from inappropriate trust alignment (i.e. over-trust or under-trust) and may result in avoidance (under-trust) or overconfidence (over-trust). The behavioural regulation is not a rational task-oriented one; rather, the regulation is goal oriented: in over-trust behaviour, one is too over-confident of one's own competencies; in the under-trust situation, one is diminishing even valid alternatives. Resulting behaviour in modelling may be, but is not limited to:

-

Promoting abilities of own model and defending model disabilities in over-trust scenarios;

-

Seemingly reliable modelling results if over-trust in own models;

-

Arguments speaking for other models neglected if over-trust in own models;

-

Diminishing other models in under-trust scenarios;

-

Diminishing people representing other models in under-trust scenarios;

-

Seeking confirming arguments for own model in over-trust and under-trust scenarios.

Factors determining trust issues can be distinguished in individual, team or leadership issues. The safety-critical impacts of such behaviour in the context of the site selection process for highly radioactive waste are:

-

Unfavourable selection of models for the assessment of the site selection;

-

Inappropriate use of the models;

-

Lack of reflection on assumptions of the models;

-

No consideration of interactions between different parameters;

-

Interpreting the results in a favourable manner;

-

Finger pointing on other models or diminishing others' opinions;

-

Exclusion of other models.

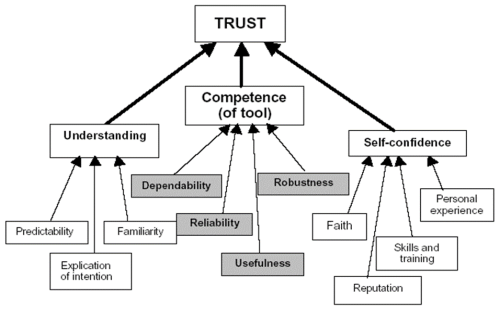

On the individual perspective, the cognitive processing cycle lets one conclude that own experiences and concepts are of importance (Straeter, 2005). Given this, Fig. 2 shows salient individual factors that determine trust, based on a study (EUROCONTROL, 2003). Self-confidence in one's own experience and concepts may lead to over-trust if one's own perspective is too self-confident; on the other hand, if too little confidence in one's own capabilities, one might under-trust oneself. A second parameter is the understanding of the situation. Finally, the capabilities of the model (respectively the competence of the tool) may determine over- as well as under-trust in one's own capabilities. The same logic holds for the capabilities of others.

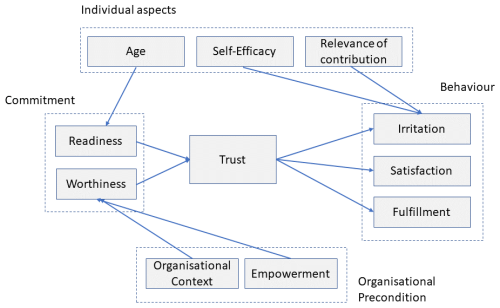

Group perspective has, in addition to the individual factors, a couple of psychological dimensions triggering trust. Jäckel (2016) investigated this with a focus on team dynamics and leadership issues, whereas leadership in this study was understood as the lead in team dynamics by a certain person (hence not necessarily the hierarchical leadership). This author concluded that trust depends on a couple of factors, shown in Fig. 3.

2.3 Impact of trust on the reliability of the modelling process

A case study conducted together with the Department of Geomechanics and Multiphysical Systems of TU Clausthal showed the safety-critical impact of trust on modelling results for a key parameter in the design of the vessel used for the final disposal of radioactive waste (Muxlhanga et al., 2024).

As part of the TRANSENS project, numerical simulations of a disposal roadway for a radioactive waste repository demonstrated that there is significant individual influence on the simulation results, even if the same technical conditions (material data, material models, simulation tool) are applied. The experiments revealed an uncertainty factor of 1.2–2.5 for the target variable of the vertical convergence. This uncertainty was the result of a simple determination of an amplification factor (slope of a straight-line equation) based on a series of approximately 14 data points. The results are highly relevant for modelling creep processes and their impact on the computationally determined load-bearing behaviour of a roadway in a Salinar Mountain.

In line with the aforementioned modelling phases (see Fig. 1), the parametrisation of the model was addressed in this study. The general conclusion of this study is that influences based on individual decisions and approaches of the respective modeller should be considered in the modelling, as these have safety-relevant effects on the design of a repository.

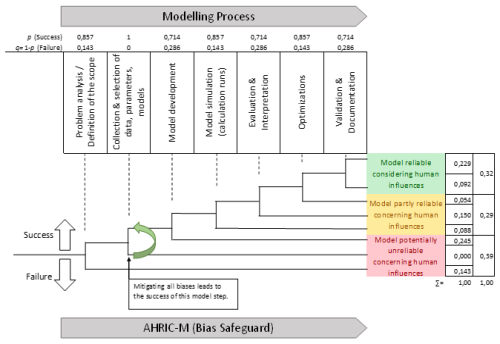

Figure 4 shows how this can be implemented in an assessment. The various modelling phases can be viewed as system functions summarised in a flowchart. Flowcharts are commonly used to describe safety-related impacts in complex systems (e.g. GRS, 1989). System functions can function (correct trust scenarios) or fail (over- or under-trust scenarios). Overall, the general modelling flowchart results in various safety-relevant end states of the model.

Trust issues lead to biases that might impact the reliability of a modelling process and hence may determine the outcome of the judgement of best possible safety of a final disposal site. A systematic assessment and mitigation of such biases are therefore required. The following section outlines a method for dealing with trust issues and biases in the current phase of site selection.

3.1 Assessment of biases

The Assessment of Human Reliability in Concept phases (AHRIC) method was developed to identify uncertainties due to human factors and to evaluate the described biases in the context of geological modelling. The starting point was the issue of uncertainties within the framework of the URS research cluster (“Uncertainties and Robustness with regard to the Safety of a repository for high-level radioactive waste” – see https://urs.ifgt.tu-freiberg.de/en/home, last access: 1 July 2025; Kurgyis et al., 2024). The issues relating to this cluster and the site selection in general present the following challenges, among others:

-

No existing system that could be assessed at present or in the coming decades;

-

Complex model calculations for long-term analyses based on parameters with a wide range (e.g. rock parameters);

-

Dependencies and interactions between the different barriers for the safe containment of waste (e.g. containers and host rock as barriers).

AHRIC enables the assessment and increase of human reliability throughout the modelling phases described in Fig. 1. This provides a comprehensive view of human reliability that previous methods have not covered. The AHRIC method is a self-assessment questionnaire designed for all modelling activities in the site selection process. It is a universally applicable framework that can be applied to a variety of system developments and industries. Therefore, in addition to geological models, it is also possible to evaluate all other conceivable modelling activities in the context of nuclear waste disposal.

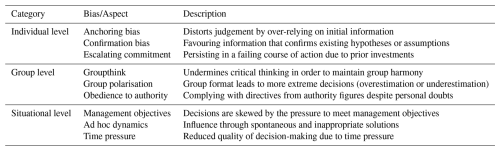

The contents have been compiled from the literature on human information processing in such modelling processes and following the classical steps of questionnaire development (Bühner, 2021). AHRIC is divided into three primary categories, each of which has its own set of aspects (biases). Table 2 provides an overview of AHRIC and presents an excerpt of its contents. Additionally, the significance of the bias or aspect is described in simplified terms, with each being predominantly measured using two items.

A well-known example of the first main category is the confirmation bias. It describes the unconscious human tendency to search for information in a one-sided manner and to interpret it in such a way that an assumption or hypothesis, once made, is confirmed (Evans, 1990). This process unfolds through three key tendencies (Hager and Weißmann, 1991):

-

Preferential selection of confirmatory information (e.g. targeted search for data that fit the model assumption);

-

Enhancing the value of confirmatory and matching information (e.g. studies that show matching data are given greater value);

-

Interpretation of contradictory information as confirmatory information (e.g. reinterpretation of unexpected model results according to own expectations).

In the second main category, the phenomenon of groupthink is an important component. The desire for uniformity in cohesive groups becomes so strong that realistic decisions are made more difficult and decision alternatives are disregarded (Janis, 1971). Groupthink is a phenomenon that occurs irrespective of the abilities of the group members, such as intelligence or experience. It can lead to management errors, even in large corporations (Peterson et al., 1998). The result is an unreliable decision-making process or a decision of poor quality.

In the third main category, management objectives that must be achieved despite internal contradictions serve as an example. In addition, time pressure plays a role as a classic trigger for goal-oriented behaviour. These aspects must be additionally accounted for in the context of trust in models, as they contribute to an increased probability of biases emerging.

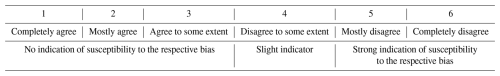

In principle, all aspects of the AHRIC method are formulated for self-assessment, so that the statements are answered by the persons concerned. This makes it possible to evaluate one's own modelling. On the one hand, this enhances confidence in one's own modelling; on the other hand, it can strengthen the trust of other scientists or the general public in the modeller. There is a 6-point Likert scale available for responding to self-statements. These statements are rated in terms of the level of agreement with them. Disagreement with an item (e.g. “I have made specific considerations that contradict the initial information.”) is interpreted as an indication of the corresponding bias, in this case the anchoring bias. Table 3 shows the systematics of AHRIC.

This classification system has been developed for the purpose of achieving measurement sensitivity, allowing for a more precise interpretation of results. Simultaneously, the system has been designed to be straightforward and uncomplicated. This is important for the interpretation of the results. In the web-based version of AHRIC, the interpretation is carried out automatically by a back-end algorithm. In a paper-based survey, the users of the method can easily carry out the interpretation themselves.

In order to address the factors that determine trust, as described in Sect. 2.2, the AHRIC method is available in two versions.

-

AHRIC-M (medium version) takes 8–12 min to complete.

-

AHRIC-S (short version) takes approximately 2 min to complete.

As a self-assessment tool, AHRIC-M contains all the essential components to assess one's own reliability in the context of modelling. AHRIC-S is available for teams, groups or departments. This version focuses primarily on aspects of group dynamics as a tool for monitoring group resilience. This makes it possible to evaluate group meetings or decisions quickly, for example, at all modelling milestones.

3.2 Procedure of an application in modelling

AHRIC provides an assessment framework for each modelling stage. An example of how it can assess an overall project management process is demonstrated in Fig. 5. For the success probabilities, shown in Fig. 5, hypothetical values are assumed. A success probability of p = 0.857 indicates that six out of seven biases are unremarkable, while one bias dominates in the corresponding modelling phase. In the second modelling step, p = 1 is assumed as the success probability. The right-hand column shows that the outcomes are derived from multiplying the probabilities.

There are various ways to manage and execute modelling, such as using classical or agile methods. Regardless of the specific approach, both AHRIC-M and AHRIC-S can be used to assess human reliability in a goal-oriented manner.

AHRIC-M is designed primarily for individuals to evaluate their own activities at reasonable intervals, such as every 6 months or at appropriate milestones or modelling stages (i.e. decision points).

AHRIC-S, the short version, offers a valuable opportunity to assess group reliability and contribute to group resilience and trust throughout all steps involving collective discussion and decision-making.

Such group processes typically take place in the context of developments, e.g. in the form of weekly meetings. Ongoing evaluation within the group can also lead to a progression of data from which it can be seen, for example, that group members are thinking and judging in an increasingly uniform and adapted way. In terms of group polarisation, this usually leads to more extreme and risky decisions (Jonas et al., 2014).

Looking at the contribution made by AHRIC to the modelling process, it is possible to evaluate the success or failure of models. This relates to human influence and results from the number of biases present in each step of the modelling process. An example of such a representation, using hypothetical data to illustrate the individual steps of the modelling process, showed the relevance and fit to the observable date in project management (Dierig, 2014). Mitigations can be achieved in two ways using AHRIC:

-

Using AHRIC-M as a bias safeguard if measurements result in no show of bias; or

-

Bias mitigation based on recommendations derived from AHRIC outcomes.

Such a correction is, of course, possible at any step, as long as the biases are evaluated in a timely manner during the progress of a project. Overall, the approach ensures a straight and timely project process of high quality with minimal latencies, which is required for the site selection process of the final repository.

The paper discusses the importance of considering human reliability in the modelling activities for localising the final repository for high radioactive materials in Germany. It states that human impacts in the modelling, the parametrisation and the interpretation of results will play a key role in fulfilling the requirement of the final disposal act and of not failing to find the location for best possible safety.

The psychological influences discussed can be classified using the terms “trust” and “biases”. Influences can stem from:

-

Hierarchies, which lead to restrictions in expressions of opinions or dependence on leadership behaviour;

-

Groupthink, which leads to an incomplete information search or lack of inclusion of alternative points of view;

-

Conflicting goals, which lead to social pressure or heurisms (mental shortcuts).

Securing the reliability of the modelling process requires the assessment and mitigation of human aspects in the modelling process by applying human reliability assessments on goal-oriented behaviours which is capable of assessing the modelling processes. The AHRIC method allows for this by monitoring biases and trust issues in the modelling process. The method consists of a questionnaire that can be used either as a self-monitoring tool or as an independent assessment of the impact of biases and trust on modelling activities.

The tool fosters a representative and diverse set of experts and/or tools, an open-minded team and a review process as well as a positive safety culture and climate. Here, open-minded discussions of the pros and cons of models, self-reflection and mutual learning is enabled – features required by the final disposal act to avoid hazardous developments in the search process. Overall, the suggested approach is an important element of resilience and seeks to avoid drift-into-failure scenarios (Seidel, 2024).

If the AHRIC self-assessment tool is used for the phases of modelling, the results allow statements to be made about the existence of one or several biases. For a group, for example, after the individual values are aggregated to the mean, the result could be that a methodological bias (“We've always done it that way”) and the described phenomenon of group polarisation apply. Even though cognitive biases cannot be entirely avoided, their impact can be reduced when AHRIC is applied in a structured and systematic manner that fosters an awareness of the underlying processes.

Overall, at the end of the development process, a model emerges that is reliable, partially reliable or unreliable in terms of human reliability issues. Based on the results and nature of biases revealed by the assessment, specific mitigation measures can be identified to overcome the safety-critical outcomes of biases in a modelling sequence or the planning process in general. The AHRIC methods also include recommendations for mitigating the identified biases. These are immediately presented to the users afterwards.

Readers interested in the underlying data are encouraged to ask BGE Germany for access using the funding code STAFuE-21-4-Klei.

OS and FF contributed equally to this work. OS planned the research activity and focussed on the human reliability issues in the modelling process. FF developed the methodology and focussed on the systematic assessment and mitigation of biases using AHRIC. OS and FF wrote and edited the paper.

The contact author has declared that neither of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This article is part of the special issue “Trust in Models”. It is a result of the “Trust in Models” workshop series, Berlin, Germany, 2022–2025.

The work was sponsored by BGE Germany within the context of a graduate project to support the German site selection process, with research on uncertainties in the selection process (funding code STAFuE-21-4-Klei).

This paper was edited by Ingo Kock and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Bühner, M.: Einführung in die Test- und Fragebogenkonstruktion, 4. Aufl., Pearson Studium, ISBN 978-3-86894-326-9, 2021.

Dierig, S.: Projektkompetenz im Unternehmen entwickeln – Eine Längsschnittstudie zur Entwicklung von projektunterstützenden Rahmenbedingungen und einer projektfreundlichen Unternehmenskultur in einem Technologieunternehmen, Dissertation, Universität Kassel, Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, Berlin, ISBN 3865738788, 2014.

Englisch, F.: Diagnostik zur Gestaltung von Einflussfaktoren auf individuelle und kollektive Biases in strategischen Entscheidungsprozessen, Schriftenreihe Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie, https://doi.org/10.17170/kobra-202403269876, 2024.

EUROCONTROL: Guidelines for Trust in Future ATM Systems: Principles, HRS/HSP-005-GUI-03, Eurocontrol, Brussels, HRS/HSP-005-GUI-03, 2003.

Evans, J. S. B. T.: Bias in Human Reasoning: Causes and Consequences, Psychology Press, ISBN 0863771564, 1990.

Fritsch, F.: Selbstbewertung als Methode zur Steigerung der menschlichen Zuverlässigkeit: Eine methodische Ergänzung der HRA-Verfahrenslandschaft, in: 32. VDI-Fachtagung Entwicklung und Betrieb zuverlässiger Produkte, VDI-Wissensforum, VDI-Berichte 2448, 71–82, VDI-Verlag, Düsseldorf, ISBN 978-3-18-092448-9, 2025.

GRS: Deutsche Risikostudie Kernkraftwerke Phase B – eine zusammenfassende Darstellung, GRS, Köln, ISBN 3923875223, 1989.

Hager, W. and Weißmann, S.: Bestätigungstendenzen in der Urteilsbildung, Verlag für Psychologie, Hogrefe, ISBN 9783801703530, 1991.

Jäckel, A.: Gesundes Vertrauen in Organisationen – Eine empirische Untersuchung der Vertrauensbeziehung zwischen Führungskraft und Mitarbeiter, Dissertation, Universität Kassel, Springer, Heidelberg, ISBN 978-3-658-19253-2, 2016.

Janis, I.: Groupthink Among Policy Makers, in: Sanctions for Evil, edited by: Sanford, N. and Comstock, C., Beacon Press, Boston, 71–89, ISBN 080704167X, 1971.

Jonas, K., Stroebe, W., and Hewstone, M. (Eds.): Sozialpsychologie, Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41091-8, 2014.

Kurgyis, K., Achtziger-Zupančič, P., Bjorge, M., Boxberg, M. S., Broggi, M., Buchwald, J., Ernst, O. G., Flügge, J., Ganopolski, A., Graf, T., Kortenbruck, P., Kowalski, J., Kreye, P., Kukla, P., Mayr, S., Miro, S., Nagel, T., Nowak, W., Oladyshkin, S., and Rühaak, W.: Uncertainties and robustness with regard to the safety of a repository for high-level radioactive waste: Introduction of a research initiative, Environmental Earth Sciences, 83, 82, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-023-11346-8, 2024.

Muxlhanga, H., Othmer, J. A., Straeter, O., Lux, K.-H., Wolters, R., Feierabend, J., and Sun-Kurczinski, J.: Ein erster methodischer Ansatz zur Identifikation von Ungewissheiten bei der individuellen Durchführung der Materialparameterermittlung für numerische Simulationen aus arbeitspsychologischer Sicht, in: Entscheidungen in die weite Zukunft. Ungewissheiten bei der Entsorgung hochradioaktiver Abfälle, edited by: Eckhardt, A., Becker, F., Mitzlaff, V., Scheer, D., and Seidl, R., Springer, Heidelberg, 283–312, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-42698-9, 2024.

Peterson, R. S., Owens, P. D., Tetlock, P. E., Fan, E. T., and Martorana, P.: Group Dynamics in Top Management Teams: Groupthink, Vigilance, and Alternative Models of Organizational Failure and Success, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 73, 272–305, https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1998.2763, 1998.

Seidel, L.: Resilienz in Managementsystemen als Voraussetzung für die Systemintegrität in Großprojekten am Beispiel der Standortauswahl für ein Endlager für hochradioaktive Abfälle, Universität Kassel, https://doi.org/10.17170/kobra-2024121010742, 2024.

Straeter, O.: Cognition and safety – An Integrated Approach to Systems Design and Performance Assessment, Ashgate, Aldershot, ISBN 0754643255, 2005.

Straeter, O. (Hrsg.): Risikofaktor Mensch? – Zuverlässiges Handeln gestalten, Beuth Verlag, ISBN 978-3-410-29548-8, 2019.

Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D.: Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases: Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty, Science, 185, 1124–1131, 1974.

VDI 4006: Menschliche Zuverlässigkeit – Teil 1: Ergonomische Forderungen und Methoden der Bewertung, Beuth-Verlag, Berlin, 2025a.

VDI 4006: Menschliche Zuverlässigkeit – Teil 2: Methoden zur quantitativen Bewertung menschlicher Zuverlässigkeit, Beuth-Verlag, Berlin, 2025b.

VDI 4006: Menschliche Zuverlässigkeit – Teil 3: Menschliche Zuverlässigkeit – Methoden zur Ereignisanalyse, Beuth-Verlag, Berlin, 2025c.